Philip Gibbs - Now It Can Be Told

“He told funny stories—one, famous in the army, called "Where's 'Arry?" It was the story of an attack on German trenches in which a crowd of Germans were captured in a dugout. The sergeant had been told to blood his men, and during the killing he turned round and asked, "Where's 'Arry?... 'Arry 'asn't 'ad a go yet." 'Arry was a timid boy, who shrank from butcher's work, but he was called up and given his man to kill. And after that 'Arry was like a man-eating tiger in his desire for German blood. He used another illustration in his bayonet lectures. "You may meet a German who says, 'Mercy! I have ten children.'... Kill him! He might have ten more."

Może się mylę, ale ostatnim czasem popularność w Polsce zdobywa szeroko pojęta literatura faktu. O ile można mówić o popularności czytelnictwa w kraju, gdzie większość ludzi nie podnosi nawet książki w roku… . Przedruki Kapuścińskiego, sukces „Białej Gorączki” Badera, twórczość Stasiuka (do której to mam zgryźliwy dystans). Swego czasu czytałem trochę klasyków reportażu wojennego (Ernie Pyle, James Cameron, Winston Churchill, Ernest Hemingway itd.), ale nikt nie zbliża się nawet do geniuszu Gibbsa. Philip Gibbs, to jedna z tych zapomnianych postaci literatury. Świadectwo tego Anglika jest niewiarygodne, brutalne i szokujące. Ostatnio przyłapałem się na tym, że ostrzegam przed makabrą, ale ta książka to już nie jest żart.

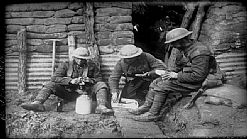

Philip Gibbs w 1914 roku został korespondentem wojennym i wysłano go na front. Gibbs był bardzo płodnym dziennikarzem i napisał cztery książki w czasie trwania wojny. Philip był pod stałym nadzorem cenzorów, którym musiał zdawać dzienne impresje na temat konfliktu (przesyłane dalej). Na początku cenzura miała polegać na „nie zdradzaniu” istotnych informacji wrogowi przez publiczną prasę (pogoda, uzbrojenie, ruchy wojsk, posiłki z innych kontynentów itd.), ale z czasem cenzorzy zawładnęli zadaniem naszego bohatera. Gibbs pisał dziennik i książki w czasie wolnym od produkowania tendencyjnych i suchych notatek „Now It Can Be Told”, to książka wydana dopiero po wojnie i zawiera ona historie, które nie mogły zostać opublikowane ze względu na morale wojska. Ciężko opisać to dzieło i czuję, że mi się nie uda. Zadziwiająco współczesna, szczera, bolesna, wymykająca się szufladkowaniu, pozbawiona w pewnym sensie komentarza. Chyba można ją przybliżyć tylko przez pocztówki, które pozostawił Gibbs. Jak na przykład oblężenie Ipr:

"Carry on there," said a young officer at the head of his company. Something in his eyes startled me. Was it fear, or an act of sacrifice? I wondered if he would be killed that night. Men were killed most nights on the way through Ypres, sometimes a few and sometimes many. One shell killed thirty one night, and their bodies lay strewn, headless and limbless, at the corner of the Grande Place. Transport wagons galloped their way through, between bursts of shell-fire, hoping to dodge them, and sometimes not dodging them. I saw the litter of their wheels and shafts, and the bodies of the drivers, and the raw flesh of the dead horses that had not dodged them. Many men were buried alive in Ypres, under masses of masonry when they had been sleeping in cellars, and were wakened by the avalanche above them. Comrades tried to dig them out, to pull away great stones, to get down to those vaults below from which voices were calling; and while they worked other shells came and laid dead bodies above the stones which had entombed their living comrades. That happened, not once or twice, but many times in Ypres”.

Gibbs posiada talent do opowiadania historii, które zobaczył i przeżył. Philip odwiedził wiele legendarnych miejsc: Somma, Verdun, Passchendaele, Hooge, Ipr, Arras, Amiens, ale wymieniać można dalej. Odnajdziecie tutaj wspaniałe opisy wymieszane z groteskową i codzienną brutalnością wojny. Zniekształcone stosy koni przypominające martwe pająki, leżące na plecach w kałuży krwi podczas ciemnej nocy rozświetlanej przez flary i ostrzał artyleryjski. Ich nogi miały poruszać się od wybuchających pocisków i wiatru. Długie, podziemne kolejki rannych, ślepych i wymiotujących żołnierzy. Masakry jeńców, wyroki śmierci za nieposłuszeństwo i niezdolność do walki (bardzo bolało to naszego reportera), krwawiące zwłoki leżące na rozkładających się resztkach ludzkich w okopach, ciężko ranni żołnierze tonący w wolno unoszącej się wodzie po deszczu we Flandrii

“There were tunnels beneath Arras through which our men advanced to the German lines, and I went along them when one line of men was going into battle and another was coming back, wounded, some of them blind, bloody, vomiting with the fumes of gas in their lungs—their steel hats clinking as they groped past one another. In vaults each side of these passages men played cards on barrels, to the light of candles stuck in bottles, or slept until their turn to fight, with gas-masks for their pillows. Outside the Citadel of Arras, built by Vauban under Louis XIV, there were long queues of wounded men taking their turn to the surgeons who were working in a deep crypt with a high-vaulted roof. One day there were three thousand of them, silent, patient, muddy, blood-stained. Blind boys or men with smashed faces swathed in bloody rags groped forward to the dark passage leading to the vault, led by comrades. On the grass outside lay men with leg wounds and stomach wounds. The way past the station to the Arras-Cambrai road was a death-trap for our transport and I saw the bodies of horses and men horribly mangled there. Dead horses were thick on each side of an avenue of trees on the southern side of the city, lying in their blood and bowels”.

Gibbs prawie zawsze podaje daty, nazwy jednostek, miejsca potyczek, nazwiska dowódców i generałów. Książka usłana jest krótkimi wywiadami, anegdotami, obrazoburczymi żartami, epifaniami błąkającymi się na peryferiach szaleństwa. Przygody dziwnego pułkownika Ronalda Campbella, który prowadzi zajęcia z walki bagnetami oraz „hipisowską” farmę dla żołnierzy na kilkudniowych przepustkach. W swoim inwentarzu miał oswojonego niedźwiedzia (Flanagan), kury, kaczki i koty, którymi to leczył z depresji i fatalizmu żołnierzy, którzy i tak po kilu dniach musieli wrócić na front. „His results were startling, and men who had been dumb, blear-eyed, dejected, shell-shocked wrecks of life were changed quite quickly into bright, cheery fellows, with laughter in their eyes. "It's a pity," he said, "they have to go off again and be shot to pieces. I cure them only to be killed—but that's not my fault. It's the fault of war." Philip przeprowadzi Was przez praktycznie każdy aspekt I Wojny Światowej. Od sztabu głównego, po zaopatrzenie i artylerię, kończąc na żołnierzach taplających się w błocie. Nasz korespondent ma niewiarygodny dar do zrozumienia ludzkiej psychiki, która jest zaminowana takimi pojęciami jak ojczyzna, religia, obowiązek, poświęcenie. Gibbs wciąż opisuje XIX wiecznych ludzi, ale sam jest zupełnie „współczesnym człowiekiem”. Jeżeli będziecie czytać uważnie, to po czasie zobaczycie jak Philip powoli sobie już nie daje rady. Zdarzenia, których był świadkiem wpłynęły na niego bardzo mocno. Podczas oblężenia Amiens Gibbs piszę swoje rzeczy w starym zniszczonym hotelu. Czasem wstaje od biurka i patrzy przez okno na miasto niszczone ostrzałem i wraca do swojej białej kartki, kontemplując skale i szaleństwo tej rzezi. „I went up to a bedroom and lay on a bed, trying to sleep. But it was impossible. My will-power was not strong enough to disregard those crashes in the streets outside, when houses collapsed with frightful falling noises after bomb explosions. My inner vision foresaw the ceiling above me pierced by one of those bombs, and the room in which I lay engulfed in the chaos of this wing of the Hotel du Rhin”. Podczas tych długich nocy Gibbs myśli o swoim nastoletnim synu, który niebawem może być już pobrany do wojska, a końca wojny nie widać. Reporter żył nieraz pod ostrzałem, został prawie zabity przez kontratak niemieckich wojsk oraz wylądował w szpitalu, ponieważ pogryzły go podczas snu w ruinach insekty żywiące się ludzkim mięsem. Nasz dziennikarz prawie nigdy się nie skarży na swój los, ale psychicznie niszczyła go rzeź ludzi, bo był on religijnym człowiekiem. Często będzie pisał, że widział tych chłopców, podawał im dłoń na powitanie, tylko po to, aby później odnaleźć ich zmasakrowane ciała w okopach. They were just schoolboys, but with the gravity of men who knew that life is short. I watched their young athletic figures, so clean-limbed, so full of grace, as they threw the ball, and had a vision of them lying mangled. Philip był świadkiem apokaliptycznych scenerii, z których spoziera prawdziwe szaleństwo:

„I remember now the intense silence of the Grande Place that day after the gas-attack, when we three men stood there looking up at the charred ruins of the Cloth Hall. It was a great solitude of ruin. No living figure stirred among the piles of masonry which were tombstones above many dead. We three were like travelers who had come to some capital of an old and buried civilization, staring with awe and uncanny fear at this burial-place of ancient splendor, with broken traces of peoples who once had lived here in security. I looked up at the blue sky above those white ruins, and had an idea that death hovered there like a hawk ready to pounce. Even as one of us (not I) spoke the thought, the signal came. It was a humming drone high up in the sky”.

Zatrzymajmy się na chwilę. Trzech korespondentów wojennych spogląda na ruiny wielkiej fabryki w Ipr, jakby była to stolica dawnej i zapomnianej cywilizacji. Oni są nieproszonymi gośćmi w innym świecie, w którym zamiast deszczu spadają pociski artyleryjskie, a po powierzchni snuje się trujący gaz. To nie jest już Ziemia, ale dziwna przeklęta planeta, gdzie śmierć spada z nieba w postaci stali. Podróż w kosmos, jeżeli ktoś lubi astronomię, to z pewnością znajdzie jakiś prawdziwy odpowiednik tej wizji. Nie zawsze jednak będzie panował mroczny klimat w „Now It Can Be Told”. Philip zabierze Was czasem na przepustkę ze zdziczałymi żołnierzami, którzy przyklejeni do szyb oglądają lśniące towary i napięte łydki kobiet w szpilkach - zaledwie kilkadziesiąt kilometrów od frontu. Żołnierze zakładają się kto zginie albo zostanie ranny pierwszy, bo dla nich była to loteria. Gibbs wiele uwagi poświęci na analizowaniu poczucia humoru. Według niego jest to ostatni bastion normalności wobec nieustannej groźby śmierci wiszącej w powietrzu (dosłownie). Obrazoburcze porównania, zupełny brak wiary w państwo czy religie, witanie się z oderwanymi kończynami podczas kopania okopów w chaplinowskim stylu, świętokradcze uwagi podczas zabijania, delektowanie się małymi detalami śmierci, ironiczne uwagi kierowane do rannych przyjaciół, groźby wobec polityków i księży naszpikowane nienawiścią i cynizmem. Wielu żołnierzy wierzyło w magiczne przesądy (np.: twoje imię musi być napisane na pocisku). Inni popadli w ponury fatalizm, jak tzw. Old Contemptibles (zawodowa armii wysłana do Francji w 1914 roku – jej straty szacuje się na 75%- 95%.), wielu z nich nic nie robiło sobie z ostrzału, ale nie dlatego, że się go nie bali, ale dlatego, że była to dla nich loteria nie warta szargania sobie nerwów. Oto opowieść o jednej z wielu kompani braci

“I came to know them all after this battle, and gave them fancy names in my despatches: the Georgian gentleman, as handsome as Beau Brummell, and a gallant soldier, who was several times wounded, but came back to command his old battalion, and then was wounded again nigh unto death, but came back again; and Honest John, slow of speech, with a twinkle in his eyes, careless of shell splinters flying around his bullet head, hard and tough and cunning in war; and little Ginger, with his whimsical face and freckles, and love of pretty girls and all children, until he was killed in Flanders; and the Permanent Temporary Lieutenant who fell on the Somme; and the Giant who had a splinter through his brain beyond Arras; and many other Highland gentlemen, and one English padre who went with them always to the trenches, until a shell took his head off at the crossroads”.

Nasz reporter rozmawiał z ważnymi niemieckimi jeńcami wojennymi na początku 1915 roku. Więźniowie mówili, że Niemcy będą bronić się jeszcze co najmniej dwa lata. Gibbs wybucha śmiechem i mówi, że są szaleni i jest to niemożliwe, bo skończyło by się to anarchią, buntem armii i dezintegracją społecznego porządku (nawet John Maynard Keynes tak twierdził). Dopiero po czasie Philip przyznaje, że to on był szalony i nierozgarnięty. Bunty wybuchły w armii francuskiej dopiero w 1917 roku po ofensywie Nivelle'a, która okazał się być katastrofą. Ciężko zresztą nazwać to buntami. Pomyślcie o tym bardziej w kategorii strajku zawodowego, gdzie żołnierze mówią, że ich życie nie będzie rzucane w błoto przez niekompetentnych dowódców w kolejne ataki (setki tysięcy ludzi przypomnijmy i to nie pierwsza nieudana ofensywa). Wojsko brytyjskie nie miało takiego momentu, ale żyło nienawiścią do swoich dowódców. Przeto ostatnia historia:

“A few minutes before our meeting a shell had crashed into a bath close to their hut, where men were washing themselves. The explosion filled the bath with blood and bits of flesh. The younger officer stared at me under the tilt forward of his steel hat and said, "Hullo, Gibbs!" I had played chess with him at Groom's Cafe in Fleet Street in days before the war. I went back to his hut and had tea with him, close to that bath, hoping that we should not be cut up with the cake. I had heard before some hard words about our generalship and staff-work, but never anything so passionate, so violent, as from that gunner officer. His view of the business was summed up in the word "murder." He raged against the impossible orders sent down from headquarters, against the brutality with which men were left in the line week after week, and against the monstrous, abominable futility of all our so-called strategy. His nerves were in rags, as I could see by the way in which his hand shook when he lighted one cigarette after another. His spirit was in a flame of revolt against the misery of his sleeplessness, filth, and imminent peril of death. Every shell that burst near Henin sent a shudder through him. I stayed an hour in his hut, and then went away toward Neuville-Vitasse with harassing fire following along the way. I looked back many times to the valley, and to the ridges where the enemy lived above it, invisible but deadly. The sun was setting and there was a tawny glamour in the sky, and a mystical beauty over the landscape despite the desert that war had made there, leaving only white ruins and slaughtered trees where once there were good villages with church spires rising out of sheltering woods. The German gunners were doing their evening hate. Crumps were bursting heavily again amid our gun positions”.

Może najpierw krajobraz. Front, ziemia niczyja, ostrzał artyleryjski, martwe ciała wokół. Gibbs jest gdzieś na froncie. Nagle pocisk trafia w polową łaźnie, gdzie myją się żołnierze. Woda, krew, flaki, kończyny i deski pływają w kraterze. Gibbsa poznaje znajomy, bo grali niegdyś w szachy w kawiarni. Henin mówi coś na pozór chodźmy trochę dalej do mojej „szopy”, bo jak spadnie kolejny pocisk to dostaniemy ciastem (tj. krwią, kończynami, szrapnelem i flakami) Oczywiście nikt nie gwarantuje bezpieczeństwa. Widać, że Henin jest już na skraju wytrzymałości psychicznej. Pali nerwowo papierosy, gdy wybucha gdzieś blisko pocisk, to wspinają się po nim drgawki, co zwiastuje z wolna shellshock. Henin ma już zupełnie dość, ogarnia go szał, gdy widzi kolejnych ludzi pchających się w ziemie niczyją. Później ci pechowcy leżą ciężko ranni i skomlą, jak zwierzęta dopóki nie trafi ich litościwy pocisk albo nie zaleje ich deszcz w leju. Dla niego wysyłanie ludzi do walki w takich warunkach to morderstwo i ludzie odpowiedzialni za to powinni zapłacić. Gibbs rozmawia z nim godzinę i idzie dalej w otchłań cierpienia, której nie potrafi zgłębić.

Taka jest ta książka. Historie, które wybrałem w cytatach nie są specjalne – są ich setki w „Now It Can Be Told”. Z pewnością jest to najbrutalniejsza rzecz jaką czytałem, ale w szerszym rozrachunku naprawdę warto. Gibbs przeżył wojnę i dorobił się (dopisał się) tytułu szlacheckiego za swoją niewiarygodną twórczość. „Now It Can Be Told” jest dostępne za darmo w projekcie Gutenberga. Po sieci krąży darmowy audiobook od librivox, więc czemu nie zapoznać się bliżej z tą całkiem zdumiewającą książką.

“Now the excitement has gone out of it, and the war looks as though it would go on forever. At first we all searched the papers for some hope that the end was near. We don't do that now. We know that whenever the war ends, this year or next, this little crowd will be mostly wiped out. Bound to be. And why are we going to die? That's what all of us want to know. What's it all about? Oh yes, I know the usual answers: 'In defense of liberty,' 'To save the Empire.' But we've all lost our liberty. We're slaves under shell-fire. And as for the Empire—I don't give a curse for it. I'm thinking only of my little home at Streatham Hill. The horrible Hun? I've no quarrel with the poor blighters over there by Hooge. They are in the same bloody mess as we are. They hate it just as much. We're all under a spell together, which some devils have put on us. I wonder if there's a God anywhere."

P.S. Musicie mi wybaczyć chaotyczność i rozklekotanie tego tekstu, bo jestem chorawy trochę.

więcej na temat

- Jak szybko tonie transatlantyk - recenzja książki "Tragedia Lusitanii"

- Battlefield 1 - na Zachodzie ze zmianami!

- Przed premierą Battlefield 1 - ciekawostki z I wojny światowej cz.2

- Gry poprzez wieki #6 – początek XX wieku

- Battlefield 1 - I wojna światowa - pustynne bitwy i zadziwiające fakty o tym konflikcie

- Jak bardzo Battlefield 1 jest wierny historii

- Czołgi, samoloty, okręty - narzędzia zagłady I wojny światowej, część II

- Narzędzia zagłady I wojny światowej - czym powalczymy w grze Battlefield 1

- Good-Bye to All That, czyli Valiant Hearts

- Kilka refleksji o alternatywnych kolejach dwóch Wojen Światowych XX wieku w grach